When Standards Feel Like Chaos

You've just inherited your institution's archives. Congratulations! Three centuries of letters, manuscripts, and photographs are now your responsibility—along with one deceptively simple request from leadership:

"Put everything online and make it searchable."

So you do what any archivist or librarian would do: you Google, or more likely, spiral down an endless rabbit hole of ChatGPT, Claude, or your favorite flavor of AI.

Within minutes, you're knee-deep in alphabet soup: Dublin Core, MODS, EAD, RAD, METS, PREMIS, FADGI, ISO 23081, and something called OAIS.

It's overwhelming, even with AI's "expert" summaries, tables and assurances that you've struck gold. But here's the truth: none of these standards exist to confuse you. They exist to protect you—and your data—from chaos.

The Hidden Cost of Making It Up As You Go

Imagine you create your own metadata structure:

| Field | Example |

|---|---|

| Item Name | "Letter from Mother Agnes" |

| Date-ish | "1890s?" |

| Who Made It | "Sr. Mary Agnes" |

| Where Found | "Trunk in Convent Attic" |

It's easy to understand—for now.

But what happens when your institution migrates systems, or joins a national portal, or collaborates with another archive?

Each institution's homegrown schema becomes its own dialect. One says creator, another says maker, a third says author. Machines can't tell they mean the same thing. Your metadata, painstakingly entered, becomes a beautiful but isolated language—intelligible only within your system.

That's what metadata standards prevent.

Standards as the Grammar of Digital Heritage

Metadata standards are the grammar of digital preservation. They don't stifle creativity—they make communication possible. Yes, any new grammar can be daunting, particularly if it's a whole new language, but once you understand the basics, suddenly you can communicate with anyone.

While studying Italian years ago, I met a lovely native Italian on a train from Umbria to Rome. She didn't speak English. Unfortunately, I had only learned up to the present tense and my vocabulary was pathetic. Nevertheless, with just that one structure—present tense—and some expressive hand gestures, we sparked a friendship that endured. So don't think that you need to understand every standard before you start generating metadata.

Here are some common structures in the metadata landscape:

Dublin Core gives everyone a shared basic vocabulary—a way to describe any resource in fifteen universal fields.

MARC 21 remains the backbone of library catalogs worldwide—the venerable standard that's powered bibliographic description for decades.

MODS and EAD or RAD extend that grammar for libraries and archives that need richer, domain-specific nuance.

METS becomes the syntax, wrapping everything together—descriptive, technical, and preservation metadata in one coherent package.

TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) provides structured encoding for textual transcriptions.

PREMIS adds the verbs—documenting what happened to a digital file: who touched it, what preservation actions were taken, and when.

ISO 23081 defines the context, ensuring every record remains authentic, accountable, and traceable across systems.

OAIS (ISO 14721) provides the architecture, defining how digital information should move from ingest to preservation to access—ensuring long-term survival.

FADGI and MIX (NISO Z39.87) describe the camera settings and imaging metadata that prove your digital surrogate faithfully represents the original.

And the newer generation of standards is emerging to meet web-native needs: JSON-LD (i.e., Linked Data, including frameworks like BIBFRAME) makes your metadata readable by search engines and AI systems, IIIF enables cross-institutional image comparison, and RiC-O (Records in Contexts Ontology) represents the International Council on Archives' ambitious reimagining of archival description—moving beyond EAD's hierarchical trees to express complex relationships as linked data.

Each plays a part in a vast grammatical system that makes digital heritage readable across generations. You don't need to master them all—start with the basics, and expand as your program matures.

The Critical Distinction: Archival vs. Bibliographic Description

Before you can choose which "grammar" to use, you need to understand a fundamental split in how heritage institutions describe their materials:

Libraries describe published items—books, journals, recordings—at the individual item level. Each book gets its own catalog record. This is bibliographic description (MODS, MARC 21).

Archives describe unique materials—manuscripts, correspondence, organizational records—using a hierarchical approach. You don't catalog each letter individually; instead, you describe the collection → series → file → item. This is archival description (EAD, RAD).

This "general to specific" approach—mandated by archival theory—is radically different from library cataloging. If you're managing archival materials, EAD (or its Canadian counterpart RAD) should be your primary descriptive standard.

Museums and historical societies often have mixed collections requiring hybrid approaches: Dublin Core for broad interoperability, EAD for archival materials, MODS for rare books.

The Electric Outlet Analogy: Interoperability

Think of metadata standards like electrical outlets.

Yes—every country could invent its own plug shape and voltage. But travel would become impossible without a suitcase full of adapters.

Standards ensure your data can "plug in" anywhere:

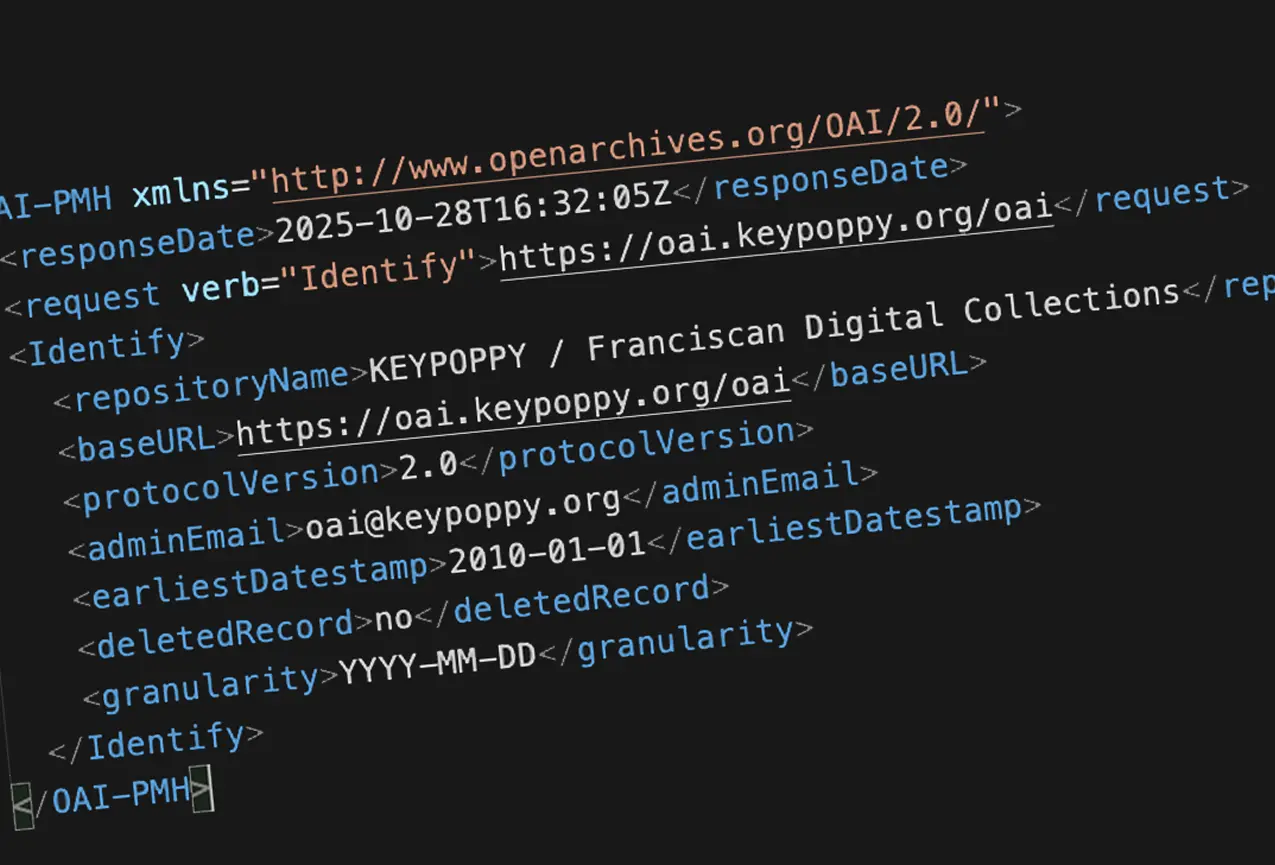

- OAI-PMH lets aggregators like the Digital Public Library of America harvest your records

- Schema.org ensures your metadata is readable by Google, Wikipedia, and AI assistants

- IIIF allows your high-resolution images to be viewed and annotated across platforms

- CIDOC-CRM (ISO 21127) connects your metadata semantically with museum, archive, and library collections worldwide

Without these standards, your beautiful digital archive becomes a walled garden—full of treasures no one can find.

The Rednal Approach: Standards at the Boundaries

Here's the nuance many institutions miss: you don't have to choose between "rigid standards" and "total flexibility."

At the National Institute for Newman Studies, we built Rednal (an archival collections management system) around IIIF for manuscript image delivery, while creating an internal structure optimized for usability. We borrowed fields from Dublin Core and MARC where they made sense, then added specialized fields our users actually needed.

The technical foundation makes this flexibility possible: Rednal uses high-memory NoSQL databases (MongoDB and Elasticsearch) where data is stored in JSON format. This means we can add, subtract, or edit fields without re-architecting database structure—a flexibility impossible with traditional SQL applications. As long as we update our API endpoints correspondingly, the schema can evolve with user needs.

But—critically—we made Rednal interoperable with external standards using OAI-PMH, JSON-LD, IIIF manifests, and custom APIs.

So institutions get an easy-to-use interface internally, but their data can still participate in the broader heritage ecosystem externally.

The Preservation Paradox

Digital preservation isn't about keeping bits alive; it's about keeping meaning alive.

Standards like PREMIS, METS, and OAIS ensure that if your current system disappears, another repository can still reconstruct the digital object's integrity—its provenance, authenticity, and fixity.

That's the difference between "we still have the file" and "we can still trust the file."

Or as preservation experts say: "If it's not documented, it's not preserved."

The FADGI Principle: Quality You Can Prove

Digitization standards like FADGI go beyond technical specifications—they're about trust.

When you digitize according to FADGI's imaging and metadata guidelines, you produce digital objects with verifiable quality—measurable against objective benchmarks.

That means:

- Consistent tone and resolution

- Standardized color targets

- Embedded technical metadata (using MIX)

- Reusable, preservation-grade TIFFs with proper Exif/XMP metadata

Without this, future users can't know whether a scan was faithful or flawed. Standards let you prove that your digital surrogates are both authentic and reproducible.

Why Standards Matter: Three Real-World Scenarios

Let's ground this in practical reality:

Scenario 1: The Grant Requirement

You're applying for an NHPRC digitization grant. The application asks: "Describe your metadata standards and long-term preservation plan."

If you answer "We use a custom Excel spreadsheet," you've just signaled that your project has no sustainability plan. Your metadata will be locked in a proprietary format, unable to be migrated, harvested, or preserved.

If you answer "We will create Dublin Core descriptive metadata wrapped in METS containers with PREMIS preservation metadata, exportable via OAI-PMH," you've just demonstrated professional competence and long-term thinking. Funding secured.

Scenario 2: The Partnership Opportunity

A state digital library wants to aggregate your collections into their portal, making your materials discoverable to millions of users. They need metadata in Dublin Core format, harvestable via OAI-PMH.

If your system can't export standards-compliant metadata, you can't participate. Your collections remain isolated, invisible to the broader researcher community.

If your system (like Rednal, AtoM, or ArchivesSpace) can export Dublin Core on demand, you're in. Suddenly your 10,000-item collection is searchable alongside 5 million items from 200 institutions.

Scenario 3: The System Migration

Your collections management software is being discontinued. You need to migrate 50,000 records to a new platform.

If your metadata is in a proprietary format, you're facing months of manual cleanup and mapping. Consultants will charge $50,000+ to write custom migration scripts. Data loss is inevitable.

If your metadata is in EAD, MODS, and PREMIS—even if stored in a now-defunct system—any modern heritage platform can import it cleanly. Migration is measured in weeks, not months, and data fidelity is preserved.

The Real Value of Standards: Interoperability, Sustainability, Trust

Standards aren't just about compliance. They're about connection and continuity.

| Value | Why Standards Enable It |

|---|---|

| Discoverability | Dublin Core + Schema.org expose your data to aggregators and search engines |

| Preservation | PREMIS + OAIS ensure digital objects survive migrations and audits |

| Reusability | FADGI + MIX enable consistent imaging workflows across institutions |

| Interoperability | METS + OAI-PMH let your data flow into other repositories |

| Trust | ISO 23081 + PREMIS provide documented provenance and authenticity |

The Quiet Power of Doing It Right

Every time you fill in a metadata field that conforms to a recognized standard, you're building a bridge—to future users, future systems, and future stewards of cultural memory.

You're ensuring that your collection isn't just online, but understood.

Think of it this way: you could save money today by skipping standards and using homegrown spreadsheets. But you'd be building a beautiful digital archive with no doors—accessible only to people physically standing inside your institution's server room.

Standards are the doors, windows, and network connections that let the world in.

And that's why standards matter.

What's Next?

Now that you understand why metadata standards matter and what they provide, the next question is: which standards do you actually need, and how do they work together?

In Part 2: The Seven Standards That Power Digital Heritage, we'll explore:

- Dublin Core, MODS, EAD/RAD (descriptive standards)

- METS (structural packaging)

- PREMIS (preservation metadata)

- ISO 23081 (administrative/records management)

- How they form an interoperable ecosystem

About This Series

- Part 1: Why Metadata Standards Matter You are here

- Part 2: The Seven Standards That Power Digital Heritage (coming December, 2025)

- Part 3: Choosing the Right Standards: A Practical Selection Guide (coming December, 2025)